January 22, 2018

Chuto Dokobunseki

Oil Markets and the Geopolitics of Saudi Arabia: Where Next?

Author

Professor Paul Stevens, Distinguished Fellow, Chatham House

Introduction

The main focus of this paper is Saudi Arabia’s role in the international oil market in the light of recent developments in the Kingdom and the global energy markets. This creates three problems of methodology. First, the story is extremely complex involving not just economics and geopolitics but also technical and engineering difficulties and various other “…ologies” ranging from anthropology to sociology. Thus it might be said that if you are not confused you do not know what is going on! Second, the geopolitics will be strongly influenced by how Washington behaves and here we are faced with “Trumpian uncertainty” whereby President Trump’s administration has no clear foreign policy but rather differing strands depending upon who President Trump last talked to. Finally, key to developments will be what is going on in Riyadh. This requires understanding the dynamics of the Al Saud, which is shrouded in mystery. As old Saudi observers often claim …”Those who talk do not know what is going on and those who know what is do not talk!” These three problems mean it is impossible to have any certainty over what is happening let alone future directions. Therefore this paper can only surmise and assume.

Saudi Arabia’s Role in the International Oil Market

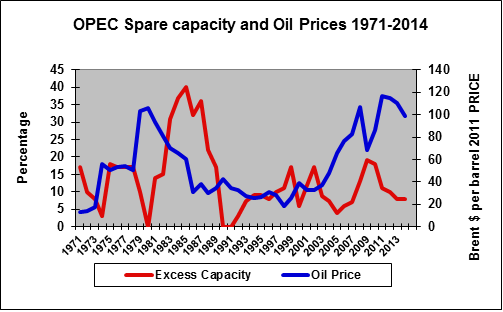

Saudi Arabia’s role in the oil market links to the relationship between oil prices and the level of spare capacity to produce crude oil. The relationship is illustrated in Figure 1

Figure 1

Source: Capacity: Author’s estimate; Prices: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2012

Spare capacity measures the level of capacity, which can be brought on-stream and into market very quickly i.e. within a matter of days. Figure 1 shows the relationship between 1971 and 2014 which is the period when OPEC was attempting to control global oil markets by managing crude oil supply. As will be developed below this control ended in November 2014 when OPEC refused to cut production faced with gross over-supply. One does not need a degree in econometrics to see a clear relationship. The tighter the market is (i.e. the lower the spare capacity) the greater the risk of a price spike and the greater the supply (i.e. the higher the spare capacity) the weaker the price. Generally, the normal state of the oil market is for it to be oversupplied requiring some mechanism to ensure that oversupply does not come to market and threaten prices.

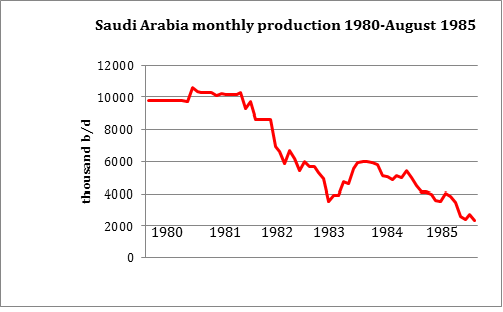

Saudi Arabia’s role in this story was to act as “swing producer”. Thus it would manipulate its production level in an effort to balance the market and thereby maintain the existing price. This occurred most explicitly in the period following the oil price shocks of the 1970s when the higher prices reduced the quantity of crude demand and increased its supply creating strong downward pressure on prices. However, as can be seen from Figure 2 this meant Saudi Arabia reducing production. Thus every time Saudi Arabia cut a barrel to protect prices, someone else increased their production by a barrel forcing Saudi Arabia to cut again.

Figure 2

Source: Middle East Economic Survey

This policy was changed in the summer of 1985 given its impact was a collapse in government revenue. However, at the start of 2011, as the Arab Uprisings began in Tunisia and spread rapidly to the rest of the Arab world Saudi Arabia quietly resumed the swing role to try and stabilize prices, albeit at a much higher level as the Arab producers required higher prices to generate the revenues to buy off growing domestic popular opposition.

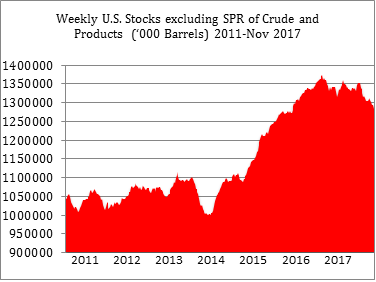

This then created “OPEC’s Dilemma”. The OPEC members needed higher prices to keep the kids out of the streets and off the squares. However, markets work! Thus these higher prices stifled demand and increased supply and therefore threatened prices. It was a re-run of the story following the oil price shocks of the 1970s. However, this time the supply-side of the story was crucial because the shale technology revolution in the United States meant production there could increase rapidly and to high levels. Between 2011 and 2016, production in the USA increased by some 4.5 million barrels per day. The result, as can be seen from Figure 3 was a dramatic increase in the levels of inventories .

Figure 3

Source: EIA Website

Initially, faced with this growing over supply, Saudi Arabia tried to use its swing role to balance the market, but as in the period 1981-85 during the summer of 2014 it simply meant Saudi production was falling and in September it abandoned its swing role. This was formalized in November 2014 when OPEC refused to agree a general cut in production. This effectively launched the oil price onto a competitive market. This was the first time this had happened since1928 when the major oil companies met at Achnacarry Castle in Scotland and agreed the “As Is” agreement. This control of the market agreed in 1928 dominated until 2014, the role being taken over from the companies by OPEC in the early 1970s.

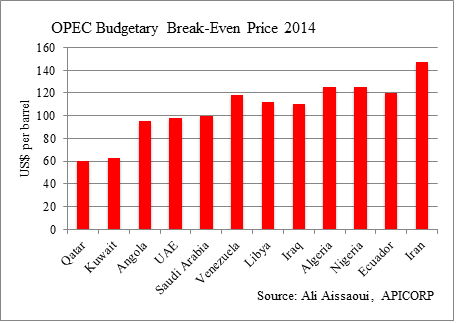

Saudi Arabia’s strategy caused much speculation about who was being targeted. Russia, Iran, Iraq and the Obama Administration were all seen as candidates. In reality it was much simpler. They wanted the supply curve to go the right way with low cost producers supplying first, leaving the higher cost producers to supply whatever remained. However, they had seriously underestimated the ability of the US tight oil producers to maintain production in the face of lower prices. At the same time, the very much lower prices meant that OPEC government were really suffering from a serious shortage of revenues. Figure 4 illustrates estimates of the OPEC budget breakeven price in the summer of 2014. Only Qatar and Kuwait could survive at $60 per barrel. The weighted average for OPEC was $102 per barrel and for Saudi Arabia was $98 per barrel. Thus Saudi Arabia came under enormous pressure to try and restore prices and was itself struggling with the lower prices.

Figure 4

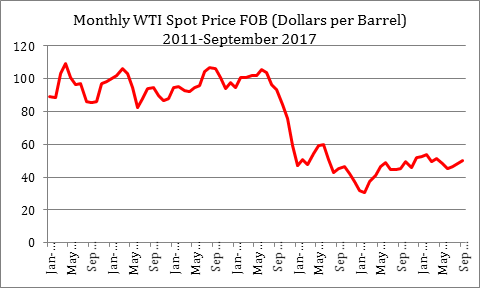

At the same time, as 2016 progressed, Saudi Aramco was finding it increasingly difficult to increase production and in October could not increase production above 10.9 million b/d. An inability to produce the barrels seriously undermined the whole Saudi market share strategy. Thus during 2016, the Saudis decided to change their policy and revert to controlling production by trying to secure a series of production constraint agreements within OPEC and also with Non-OPEC. The result, after a number of false starts, eventually was the December 2016 agreement whereby OPEC was to cut 1.2 million b/d and some Non-OPEC countries, including Russia, agreed to cut 0.6 million b/d. The market responded positively to the agreement but as can be seen from Figure 5, the price struggled to get above $40 per barrel.

Figure 5

Source: EIA Website

It is in the context of this role of Saudi Arabia in the global oil market that problems associated with recent developments in the Kingdom can now be considered

Current Challenges and Problems for Saudi Arabia

Recent Developments

In January 2015, following the death of King Abdullah, Salman bin Abdulaziz acceded to the throne. However, the key player was his son Mohammad bin Salman, popularly known as MbS . Initially he was appointed as Deputy Crown Prince with Mohammed bin Nayef (known as MbN) as Crown Prince. In June 2017, Nayef was moved out of that position and MbS became Crown Prince. He had already begun to develop a whole range of economic reforms under the headings of the National Transformation Plan (NTP) and Vision 2030. This was done with the help of a large number of consultants with McKinsey at the top of the list . The prime aim of these programmes was to diversify the economy away from dependence on oil and to generate jobs for the growing number of young Saudis entering the job market. This was also linked into a more aggressive foreign policy. The year 2015 was seen by Saudi Arabia as the “year of Shi’a encirclement”. Iran looked to be getting closer to the Obama Administration reflected in the JCPOA nuclear agreement. Assad in Syria appeared to be strengthening his position and winning the civil war. In Iraq, the Shi’a were dominating political developments. The Houthis in Yemen, allegedly supported by Iran, were beginning to try and assert their authority. In response, MbS effectively began a war in Yemen in an effort to try and break this circle.

Meanwhile, MbS was in the process of securing his position at the expense of other branches of the family. For many years the system had worked upon the basis of spreading the wealth of the Kingdom among the family by allocating Ministerial posts. Thus the Minister of the Interior, Nayef had been in post for 38 years; the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Saud bin Faisal had been in post for 40 years; the Minister of Defense, Sultan had been in post for 48 years; and the Head of the National guard, Abdullah had also been in post for 48 years. Effectively this old guard was removed and replaced either through death or dismissal and replaced by the next generation but in a way that meant power was concentrated within Salman’s (and MbS’s) grouping.

Then in November 2017 there was a much-publicized purge with a number of Princes and senior businessmen being arrested. This led to much speculation in the Western media about a power grab by MbS. This rather missed the point. The “power grab” had in fact begun in 2015 and was more or less complete by June 2017. Rather the purge probably had two motives. First, was to act as a deterrent in case others were contemplating trying to challenge MbS’s growing dominance. Second, it was also designed to indicate that the sort of corruption, which had characterized the government and country for decades was no longer acceptable. A good example of this was the arrest of Adel Faqih, Minister of Economy and Planning. Faqih had been a major intellectual influence on MbS persuading him of the value of what were essentially neo-Thatcherite policies to reform the economy. However, he had also been mayor of Jeddah at the time of the infamous floods of 2009 when over 100 people were killed .

One consequence of the purge was a capital outflow from the Kingdom putting the declining financial reserves under ever more pressure. It also raised serious concerns for inward investors over the issues of property rights in the Kingdom. It was not at all clear what the legal bases for the arrests were and indeed this became more prominent when it appeared that those arrested could effectively buy themselves out of arrest by surrendering some of their wealth.

Extending the 2016 OPEC/Non-OPEC Deal

The OPEC meeting scheduled for the 30th November will have to consider whether to extend the December 2016 deal beyond its current deadline of March 2018. The December 2016 agreement between OPEC and some Non-OPEC countries was hailed as a great achievement. Unfortunately it was too little and too late. The OPEC agreement of September 2016 in Algiers, which had under-pinned the December agreement, was based upon OPEC producing 29.8 million b/d by January 2017. However, at the time of the December agreement OPEC was already producing some 32 million b/d. Also Libya and Nigeria were excluded from the deal and they were rapidly increasing their production. By summer, they had increased production by 520,000 b/d. Furthermore compliance was rather poor. Iraq in July was 120,000 b/d over quota while Kazakhstan who had agreed a 20,000 b/d cut in 2017 by summer had increased by 140,000 b/d with more to come as Kashagan came on-stream. Russia also only managed to meet its target of a 300,000b/d cut by very late summer. Despite positive noises from the periodic meetings of the special committee created to monitor compliance, it was generally poor. In May 2017 it was agreed to extend the agreement, originally scheduled to run to June 2017, to March 2018.

However, the agreement has proved to be of limited effectiveness in reducing the supply overhang as can be seen from Figure 3. The reason is simply that the higher prices experience since late summer have prompted an increase in supply. In particular, U.S. tight oil supplies have responded to the better prices. Furthermore, they will continue to do so, not least because the producers are able to hedge higher prices thereby locking-in future supply increases. The result has been discussions over whether to extend the agreement in an effort to try and balance the market. Noises out of both Riyadh and Moscow suggest this is likely to happen. However, even if it does happen, there remains an underlying problem. History shows quite convincingly that the longer such production restraint agreements are in place, the worse the compliance gets. This means that someone, somewhere will have to resume the “swing role” to try and maintain some semblance of balance in the market. Absent this, the price will yet again come under downward pressure. The only country that could conceivably fulfil this is role is Saudi Arabia . However, history as between 1981-85 and 2011-14, shows that this cannot work on a long terms basis. It seems unlikely that MbS would agree to a policy that has no chance of eventual success.

The Saudi Aramco IPO

The proposed privatization of 5 percent of Saudi Aramco is seen as the centerpiece of Vision 2030, launched in April 2016, and the NTP, launched in June 2016. It is regarded as the key idea of Mohammad Bin Salman (MbS) and as such, if it were to fail, this would be seen as a major policy failure for MbS. Furthermore, it was announced with very little thought as to the implications of such an IPO and indeed was launched against the advice of McKinsey who were very much behind the whole economic reform programme. As this has progressed –the original announcement stated that the IPO would be launched at “the start of 2018” it has become increasingly apparent that there are serious problems with the IPO.

What is to be sold: The CEO of Saudi Aramco has said it will be 5 percent of “the whole company” but other have suggested this would not be attractive since it would include a lot of loss-making downstream assets and other activities associated with the “national mission” which are not profitable in terms of private interest. However, trying to split off the upstream from the rest would be very difficult and complex. There was also considerable concern about the lack of transparency over the company.

Valuation: Originally, MbS claimed that Saudi Aramco would be worth $2 trillion and this the 5 percent would net $100 billion which would go into the Saudi Public Investment Fund and be used to “diversify” the Saudi economy. However, it is clear this valuation was quite unrealistic. The figure was created by multiplying the estimated reserves (266 billion barrels) by a price of $7.5 per barrel, based on the estimated price paid by Total for Maersk Oil. This is a very naïve methodology and assumes the reserves would all be produced at once. Thus any time value of money is ignored. Other more realistic estimates have been far lower. However, the problem is this is MbS’s figure. Getting anything less would reflect badly on him and be regarded as a failure feeding the opposition to MbS, which is growing within the Kingdom as a result of family jealousy and unpopular economic reforms raising energy, electricity and water prices. Thus the cuts to salaries and perks in 2016 to try and cut expenditure had to be reversed in April and June of this year.

Where to float? The Oil Minister has stated the primary listing will be on the Tadawul (the Saudi stock exchange) but that its size would mean one or two other Exchanges would have to be involved. However, the two obvious candidates both have problems. New York would leave shareholders vulnerable to JASTA allowing victims of 9/11 to sue the Saudi State. Also New York has very strict regulations on how reserves are allowed to be booked – “proved undeveloped reserves” under which most of Saudi Aramco’s reserves would fall must move to development within five years. London’s rules have actually been changed to try and accommodate Saudi Aramco but these rule changes have been strongly challenged by institutional investors and anti Saudi elements driven by concern over Saudi involvement in the growing crisis in Yemen. Other Stock Exchanges have been mentioned but each is likely to have their own problems

Who will buy? It is not obvious who would be willing to buy shares in a context where they can only expect a utility rate of return. Private oil companies would have no interest given it has been stated by Minister Falih that the shareholders will not be allowed to book any reserves. Also, once the IPO has been launched the majority shareholder would have little or no interest in what happens to the share price. Selling much more than 5 percent would generate strong opposition within the Kingdom: an example of “selling the family silver”.

As this year has progressed, these problems have raised significant concerns in Riyadh that the flotation could fail. Failure would be defined as getting significantly less than the $100 billion claimed by MbS. There have been reports that Riyadh has been trying to secure “cornerstone investors” to underwrite the float. Specifically, India and China have been targeted but to date there have been little if any public indication that such a strategy would work. China and India might believe if they became “cornerstone investors” they might secure oil supplies but history does not necessarily support this view. One only has to look at the experience of Japan following the 1973 oil price shock. The Government went to huge lengths to try and “be friends” with oil producers but when the second oil price shock came in 1979-80 there was no discernable benefit. These problems collectively seriously threaten the IPO.

However, most of the problems listed earlier would disappear if the sale could be done privately. Thus the valuation would remain secret; there would be no need to meet stock exchange regulations; any transparency could be kept between seller and buyer. A private sale, almost by definition, could not “fail” which is why it would be very attractive to Riyadh. It has already been leaked informally that the IPO will not now happen until 2019. They cannot cancel it outright – too much loss of face. However, they can delay with rumors of private sales etc. If they can get a private sale on attractive terms I believe they would take it rather than risk the humiliation of a failed IPO.

Diversification and the Global “Energy Transition”

The world is currently going through an “energy transition”. This is when an economy switches from one dominant source of energy to another. There have been many such examples of energy transitions through history. One such example was the U.S. between 1865 and 1900 when the economy switched from using 80 percent wood and 20 percent coal to 80 percent coal and 20 percent wood. Another example was France between 1975 and 1990 when the economy switched from generating electricity by oil and coal to using nuclear. Normally the transition is triggered by a specific event. In the U.S. example it was triggered by a growing shortage of fuel wood and in the French example it was triggered by the first oil shock of 1973-4 giving rise to concerns over oil security. Once the initial trigger has emerged other factors reinforce the process of transition. These usually relate to changes in technology as a result of the initial trigger.

This current transition is a move away from hydrocarbon molecules to electrons. The trigger has been concern over climate changes and the Paris Agreement arising from COP21 in December 2015. The process has been and is being strongly reinforced by the technological changes reducing the costs of renewables making them now competitive with centralized thermal power stations. It is also being supported by developments in electric vehicles. Electric vehicles tick all the right boxes. They tick the security of supply box reducing a country’s dependence on supply of petroleum products. They also tick the environmental boxes: namely climate change (depending of course on how the power is generated) and also growing concern about particulate pollution and urban air quality. Finally, they provide a solution to the problem of intermittency associated with the spread of renewables since they potentially provide battery storage.

This energy transition presents a serious challenge to Saudi Arabia. Despite decades of providing lip service for the need to diversify the economy away from dependence on oil, the economy has singularly failed to do so. The reasons for this failure are many and complex. However, basically they derive from the failure to develop an effective private sector operating in the Kingdom. This is largely the result of poor property rights. Thus there is an active private sector, but much of their activities are done outside of the Kingdom for fear of not being able to secure the fruits of their labours. The issue is reminiscent of the debate in the Soviet Union at the time of Gorbachev. It was decided that the economy needed “perestroika” i.e. economic liberalization. However, Gorbachev took the view that this could not be achieved with “glasnost” i.e. political liberalization. By contrast, China welcomed the prospect of economic liberalization but rejected political reform. In Saudi Arabia and indeed much of the rest of the Arab world, the ruling elites are too entrenched in their capture of the private sector effectively stifling the prospects for a dynamic sector to reduce the very high levels of dependence on exporting oil.

Thus the energy transition presents a serious challenge to the Kingdom. Failure to diversify implies the potential presence of very large stranded assets.

There is a further dimension to the problem. The Middle East and North Africa is currently extremely unstable. Indeed, I would argue one has to go back to 1918 – the end of the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire –to find a period of similar instability. This is currently greatly aggravated by “Trumpian Uncertainty” whereby the U.S. appears to have no coherent foreign policy in the region other than to somehow seek regime change in Iran. This is feeding into increasingly poor relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran. There is a serious possibility of military conflict between the two. If this were to happen, almost certainly oil supplies would be threatened leading to an oil price shock. In that event, another oil price shock would be triggered. This would almost certainly encourage oil importing countries to implement policies to move away from oil thereby speeding up the existing energy transition. A similar process followed the second oil price shock of 1979-81 when the G7 meeting in Venice and Tokyo agreed to implement such policies, which contributed greatly to the subsequent fall in oil demand. This time such moves would be experienced in far more countries and would be more determined and effective given that in the transport sector there are growing alternatives to oil.

Conclusions

Saudi Arabia faces serious challenges. Its fiscal situation is not good. Since 2014 its foreign exchange reserves have fallen from $750 billion to less than $500 billion. Attempts to cut government spending have fallen foul of growing popular opposition. Cuts to public sector salaries and perks made in 2016 were reversed in 2017. The cuts have also pushed the non-oil economy into recession, often triggered by non-payment by Government to private contractors. MbS’s foray into Yemen is unpopular and is increasingly seen as a war that is unwinnable. Added to all this is family discord as MbS’s rise to power generates the inevitable jealousy although that has to some extent been muted and driven underground by the recent purge.

Above all, the problem is that MbS has raised expectations among the young in Saudi Arabia who are now expecting jobs and improved living standards. If he fails to deliver on this, and already the extremely ambitious targets in the NTP and Vision 2030 have been cut back, then the stability of the Kingdom must be in doubt. If nothing else, this will reinforce concerns over dependence on imported oil, which will reinforce and accelerate the coming energy transition and will further threaten stability.

* Professor Stevens gave a presentation with the same title at the JIME-IEEJ International Symposium on November 29th, 2017. On November 30th, OPEC and non-OPEC oil producers led by Russia agreed to extend oil production cuts until the end of 2018.