January 30, 2015

Chuto Dokobunseki

The Next Decade in MENA and Global Energy Markets: Turmoil and Transformation

Author

Dr. Robin M. Mills,

Head of Consulting at Manaar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis and Capturing Carbon

Head of Consulting at Manaar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis and Capturing Carbon

Introduction

The past decade has been one of the most dramatic ever in global energy markets, with major events both on supply and demand sides. These events have occurred both within the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region and outside it. Given MENA’s centrality to global energy, and the leading role of oil and gas in the region’s economies, such shifts have major geopolitical consequences. Over the coming decade, it is possible to foresee the unfolding of current trends. However, the implications of these are still not all clear and remain the topic of debate, while there is always the possibility of further unexpected changes in politics, economics and technology.

Key Factors of the Past Decade

Global energy markets over the past decade and a half have been shaped by several key factors, some of which were relatively predictable while others were unexpected to most forecasters.

Some of the most important of these factors have been:

Rapid economic expansion in Asia

This was particularly the case in China, whose fast economic growth led to similar energy demand growth, and record commodity prices, particularly for oil. From 2000 to 2008, China’s real GDP (in purchasing-power parity) rose at an annualised rate of 8.4%[1], and its oil demand rose at an annualised rate of 6.7%[2], from 4.77 million barrels per day (Mbpd) in 2000 to 7.99 Mbpd in 2008.

Growth in India was also strong, though from a smaller base, at 3.9% annually, from 2.26 Mbpd to 3.08 Mbpd, and demand in Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam also grew around 3-4% per year over the same period. By contrast, oil demand in Japan fell due to sluggish economic growth and increasing efficiency.

With China’s domestic oil production growing only 0.56 Mbpd during 2000-8, and India’s flat, the difference had to be satisfied by imports. The Asia-Oceania region imported 18.1 Mbpd of crude oil and refined products on a gross basis in 2000, and by 2008 this had reached 22.5 Mbpd[3].

This rapid growth ran up against relatively constrained supply, leading to steep rises in oil prices, from an average of $38.55 per barrel for Brent in 2000 (inflation-adjusted to 2013 dollars) to $105.23 in 2008. Briefly, during 2008, the price reached $147 per barrel before plunging during the financial crisis.

Growth has continued since the financial crisis in 2008, albeit at somewhat lower rates. Asia-Pacific now imports a net 20.2 Mbpd of oil, of which China makes up 7 Mbpd, the world’s largest importing country, having overtaken the United States.

Asia has become more and more the dominant market for MENA’s oil and gas exports, replacing the US and Europe. Of 2013 MENA oil exports of 19.6 Mbpd, just 2.1 Mbpd and 2.07 Mbpd went to traditional markets in North America and Europe, respectively. 14.9 Mbpd was exported to Asia-Pacific, of which 3.3 Mbpd to China.

Growth in gas and coal consumption was similarly marked. Asia-Pacific gas consumption rose 6.5% annually from 2000 to 2008. China’s growth was even faster, at 16% per year, and by 2004 it was already the second-largest gas market in Asia after Japan. In 2009, it overtook Japan and is now the fourth-largest gas consumer in the world. In 2000, Asia as a region had been largely self-sufficient in gas, though this concealed significant liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports by Japan from other Asian countries (Australia, Malaysia, Indonesia) as well as from the Middle East.

By 2008, the region as a whole was importing some 6.1 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/day) of gas. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan were the leading importers, but Chinese imports, including LNG as well as pipeline gas from Central Asia, were also significant. To the extent that land-locked Central Asian gas had no other outlet, this did not affect world gas markets. But growing imports of LNG were mostly met by the ramp-up of the Qatari LNG industry to be the world’s largest. Particularly following the 2008 financial crisis, and the emergence of US shale gas (discussed below), Qatari LNG exports were shifted from North America to high-priced Asian markets. Like oil, LNG prices increased sharply, from $4.72 per million British Thermal Units (MMBtu) for average Japanese imports in 2000, to $12.55 in 2008.

But gas is still only a small fraction of Chinese primary energy consumption. Most of its energy demand continues to be fuelled by coal, demand for which grew at 9.2% annually between 2000 and 2008. China now consumes 50% of world coal, and 75% of the growth in global coal consumption during 2000-2008 came in China. Though most Chinese coal is mined domestically, its growing imports also had an impact on price: from $32 per tonne for the Asian marker price in 2000, to $148 in 2008.

The high oil prices and growth in exports triggered an economic boom across much of the MENA region. Combined with subsidised prices and government-led policies of energy-intensive industrialisation, MENA’s own energy consumption rose sharply. From 2000 to 2008, the Middle East’s oil production rose by 2.7 Mbpd but its domestic oil consumption increased by 2.1 Mbpd, so that overall exports only rose slightly.

So the impact of Asian economic growth was a dramatic rise in energy consumption and imports, which manifested itself in sharp price rises across all energy sources, and a shift in trade patterns. OECD countries, including Japan as well as those in North America and Europe, generally had to adjust by reducing oil imports. This phenomenon has continued since the 2008 financial crisis, albeit at a slower pace.

Faced by rising prices and, in the case of all except Japan, their own growing demand, there was growing attention from the leading Asian economies on how to ‘secure’ their future energy supplies. Asian national oil companies typically sought to take direct equity stakes in oil and gas fields. They also extended oil-backed loans or offered to build infrastructure in return for field development rights. However, these tactics were mainly successful in Africa and Central Asia. They were less applicable in cash-rich MENA countries, where most major hydrocarbon assets are held by national oil companies or super-major IOCs.

The main exceptions were in Iran and Iraq. Japanese and Indian companies, INPEX and ONGC, negotiated for oil and gas developments but ultimately had to withdraw in the face of international sanctions. China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) commenced work on the onshore Azadegan oil-field and Phase 11 of the supergiant South Pars gas field, intended to feed the Iran LNG project, but saw its contracts terminated in 2014 for non-performance. Compatriot Sinopec retained its position in the Yadavaran oil field but by 2014 had only made slow progress in building up production.

Asian companies saw more success in Iraq. Sinopec bought Addax Petroleum, a company active in the autonomous Kurdish region, while Korea National Oil Corporation (KNOC) was awarded oil exploration blocks, having earlier entered exploration in Egypt via its acquisition of the UK’s Dana Petroleum. China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and CNPC were awarded fields in southern Iraq, along with Petronas from Malaysia, JAPEX from Japan and KOGAS from South Korea. The most notable venture was CNPC’s with BP to develop Rumaila, Iraq’s largest producing field. Mitsubishi also took a stake in the Basra Gas project with Shell.

ONGC and CNPC also teamed up to buy a stake in Shell’s Syrian assets, while Sinopec and Sinochem acquired smaller oil companies producing there. But during the civil war from 2011 onwards, they all lost control of these fields.

Petronas, ONGC and especially CNPC also developed strong positions in Sudan prior to its division. They were assisted in this by Western sanctions and human rights activism which largely prevented Western oil companies from becoming involved. The crisis in Sudan/South Sudan presented China with a significant problem, given its long-standing policy of ‘non-interference’ in sovereign affairs. Sudan was an important oil supplier to Beijing, and CNPC had made large investments in the country. This faced Chinese diplomats with the tricky task of negotiating a resolution that would allow a resumption of oil exports, without being seen to interfere overtly.

In recent years, Japan, South Korea and China all sought to develop positions in the GCC, which was more difficult given that major hydrocarbon assets in these countries rarely become available. Apart from discussions with Saudi Arabia, progress on joint-venture refineries in Asia with both the Kingdom and Kuwait, and gas exploration ventures in Saudi Arabia and Qatar, the main outcome was in Abu Dhabi. KNOC was awarded three concessions in Abu Dhabi, in part linked to its competitive offer on the Emirate’s nuclear power programme. Japanese companies had been involved in Abu Dhabi since the 1960s, and the ADOC consortium was awarded a renewal and expansion of its licence. CNPC also signed a preliminary agreement on exploration and field development. And KNOC, INPEX and CNPC were all short-listed to bid for the renewal of the onshore Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operations (ADCO) concession, which as of December 2014 had not been awarded.

However, by the post-financial crisis period, it appears that even China had become relatively comfortable in relying on the market to meet its oil needs. Major Chinese oil companies active overseas did not necessarily seek to ship their oil back to China, and indeed, deals in locations such as Kurdistan or Egypt were unlikely to have Asia as a primary market. And most of the deals made by Asian oil companies in MENA had a straightforward commercial rationale as much as, or more than, a national interest one.

Advances in renewable energy

Progress in renewable energy, particularly solar photovoltaic (PV), wind, and bioenergy, has brought it close to competitiveness with fossil fuel energy in certain markets. This is particularly a feature of the post-2008 period, since before then renewable energy remained high cost and was scaling up from a low base.

Global installed solar photovoltaic capacity in 2000 was insignificant at just 1250 megawatts (MW). By 2013, it reached 140 gigawatts (GW). Wind capacity was 17.9 GW in 2000 and grew to 320 GW by 2013. Although still low compared to conventional generation, particularly considering the much lower availability factor of solar and wind, this has reached the level of having a significant impact on certain electricity markets, such as Germany’s.

Renewable electricity generation has little direct impact on oil markets, given that little oil is used for power generation outside the Middle East and some isolated islands. But it is increasingly an alternative to generation from oil and coal. Since 1998, reported PV system prices have fallen by 6-8% per year on average[4], and the price fall was particularly steep from 2008 to 2012. PV system costs have now fallen to the level that, in a sunny climate such as that of the Middle East, they are competitive with oil and high-priced gas for power generation[5]. The growing use of renewable energy is having a negative impact on gas demand in Europe, a concern for Qatar and Algeria amongst MENA countries.

Although ambitious renewable energy plans in Saudi Arabia have made little progress, Abu Dhabi has installed one of the world’s largest concentrated solar thermal (CSP) plants, the 100 MW Shams-1, and Dubai, Jordan, Morocco and Egypt have begun to advance on installing solar PV, solar CSP and wind power. This can make a growing contribution to meeting the region’s energy demand, particularly that of the energy-importing states, so slowing the growth in domestic oil and gas consumption. However, it will be some years before renewable energy installation scales up to the level of having a meaningful impact on conventional fossil-fuelled energy use.

Growing concern about climate change

In contrast to the Kyoto agreement signed in 1997, and the failed Copenhagen talks of 2009, recent trends in climate negotiations have focussed on national or regional-level solutions. So far, outside Europe, there has been little binding legislation. European and US renewable incentives have had a major impact on advancing the competitiveness of solar and wind power, while the US’s Environmental Protection Agency’s rule on coal-fired power plant emissions will significantly increase demand for gas and other low- or zero-carbon power. The impact of the November 2014 climate pact between the US and China is as yet unclear but could lead to lower Chinese energy and coal use, and more progress on renewable energy.

Middle Eastern countries, as major oil and gas producers, initially took a relatively obstructionist attitude to climate negotiations. However, later in the period, and particularly in the case of the UAE and Qatar, they were more constructive, lobbying for policies that advanced specific national goals, such as the inclusion of carbon capture and storage (CCS) in the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). They also began setting renewable energy targets, and Abu Dhabi launched its clean energy venture Masdar in 2006.

So far, the impact of climate policy on MENA is ambiguous. By restricting the use of coal, it opens up markets for MENA gas exports. It has not yet had a major impact on oil, beyond the heavy taxation already present in Europe and Japan. In the longer term, though, it is likely further to restrict oil demand.

Global economic crisis in 2008-9

The financial crisis and subsequent recession or slow growth in many major economies, reduced both energy demand and investment. Oil prices fell from a peak of $147 per barrel to $34 per barrel in the depths of the crisis, before OPEC production cuts led to a price recovery during 2010. Several MENA countries, such as Saudi Arabia, cut back investment plans in response to lower forecast oil demand. However, other cuts by non-OPEC countries and leading international oil companies (IOCs) probably had a more significant impact on restricting production gains after 2010. Post-crisis energy demand growth, including in China, appears to be structurally lower than before the crisis.

The nuclear accident at Fukushima in Japan in 2011

In the wake of the Fukushima accident, there were consequent reductions in nuclear programmes in Japan, South Korea, Germany and other countries, increasing fossil fuel demand. Qatar in particular benefited from higher demand for its LNG, while the increased use of oil for power generation in Japan was also positive for prices.

Some MENA countries, notably Kuwait, abandoned nuclear power plans in the wake of the accident, though these were not advanced in any case. The UAE, on the other hand, pressed ahead with its civil nuclear power programme, to build a total of 5.6 GW of power between four reactors at Baraka in the Western Region (Al Gharbia), with the first to start in 2017. Saudi Arabia, Jordan and, much more slowly, Egypt, also worked on nuclear power plans. However, the region’s first working reactor, completed by the Russians based on earlier German work dating back to the 1970s, started operations at Bushehr in southern Iran in 2011. Iran’s future expansion of nuclear power was, though, clouded by international sanctions.

Nuclear power in MENA has been seen as a large-scale, relatively low-cost form of power generation not dependent on gas supplies that have been unreliable or expensive in some countries. However, most countries have not had sufficient financial, technical or political will to see projects through to construction.

Revolutions, civil war and serious unrest in several MENA countries

During 2011-14, a variety of political upheaval across the Middle East and North Africa led to interruptions in oil and gas supplies (Figure 1). Most notably in Libya, the country’s pre-war oil production of 1.6 Mbpd was almost entirely cut off during the war to remove long-time ruler Muammar Gaddafi. Though it recovered quickly after his overthrow to around 1.4 Mbpd, it was then disrupted by ‘federalist’ forces who blockaded eastern oil ports. During late 2014, oil production recovered to some 0.8 Mbpd, but was then threatened by local and tribal discontent, and by the growing conflict between the GNC previous parliament and the subsequently-elected House of Representatives.

Figure 1. Disruptions in oil production 2011-14 (EIA; Manaar research)

Libya was the leading oil and gas producer to be affected by the revolutions. But oil output in lesser producers – Syria and Yemen – was also seriously disrupted. Syrian production fell from 385 000 barrels per day (385 kbpd) in 2010, the last full year before the war, to just 56 kbpd in 2013, and Yemeni production from 291 kbpd to 161 kbpd over the same period.

However, the major Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) producers were not directly affected by the Arab revolutions, with only minor protests in Saudi Arabia and Oman that did not disrupt oil production. Major protests in Bahrain, and their subsequent repression, also did not interrupt the country’s small oil production.

Egyptian gas exports to Jordan and Israel were repeatedly cut off by bombings of the pipeline in Sinai, and then by shortages of Egyptian gas supply given a lack of previous investment in new production. In a separate issue, oil exports from the new state of South Sudan were blocked by continuing disputes with Sudan, and then by the civil war that broke out in South Sudan in December 2013.

Though not directly connected to the ‘Arab Awakening’ revolutions, US-led and international sanctions imposed on Iran over its nuclear programme also had a major impact. Iran’s crude oil production of 3.706 Mbpd in 2010[6] fell to 2.69 Mbpd in 2013 and 2.75 Mbpd in November 2014.

In turn, the Syrian conflict eventually spilled over into Iraq, with the takeover of the important city of Mosul in June 2014 by militants of the Islamic State of Iraq and Al Sham (ISIS), soon self-proclaimed the ‘Islamic State’, or known derogatively as ‘Da’esh’ in Arabic, along with their allies. This led to a shut-off of oil exports from northern Iraq via the pipeline to Turkey, and to a siege of Iraq’s largest refinery, Baiji. Operations in Kurdish oil fields near the frontline were suspended.

However, by December 2014, the military situation appeared to have stabilised under a new Iraqi government, and central government and Kurdish forces were making some limited gains against ISIS. Some small oil-fields occupied by ISIS were recovered and the siege of Baiji was lifted. Oil earnings for ISIS from fields in Iraq and Syria, estimated at $2-3 million per day early in their campaign, had dwindled to $250-350 000 per day by December 2014, as US air attacks on their refineries, attempts to crack down on oil smuggling into Turkey and the Kurdish region, the loss of fields, and natural production declines from lack of maintenance, took their toll.

The combined effect of these aggregate disruptions reached up to 2.5-3 Mbpd of lost supplies during 2011-14. It was not on the scale of past oil shocks such as the 1973-4 OAPEC embargo or the 1978-80 Iranian Revolution and Iran-Iraq War, and was compensated by use of spare capacity in Saudi Arabia and by growing US tight oil production. Nevertheless, this production loss had a significant impact in keeping oil prices elevated in a range around $110 per barrel.

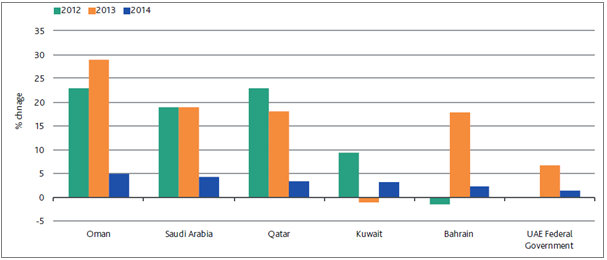

Another significant impact of the revolutionary pressures was to increase national budgets in countries seeing to avoid or contain unrest. In 2011, Saudi Arabia announced a special package of $130 billion of social spending. Following its 2011 protests, Oman boosted its budget by a quarter and created more jobs in the state sector. Governments were also reluctant to press ahead within plans to reduce energy subsidies, though Iran had executed a fairly successful reform in 2010. These spending increases came on top of a steady growth in budgets as oil revenues had grown in the 2000s, and they left the budgets of MENA oil exporters exposed to any falls in prices. However, over the past two or three years, GCC countries such as the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia managed to reduce spending or at least slow its growth (Figure 1). This left Iraq, Iran, Algeria, Oman and Bahrain as the most fiscally-exposed in the region, although Bahrain and Oman can probably count on financial support from other GCC members in the case of crisis.

Figure 2. Year-on-year spending growth in the GCC (Moody's)

Major advances in unconventional oil and gas production

Unconventional oil and gas production responded to advances in technology and the incentives provided by high prices. Unconventional sources include most notably shale/tight oil and gas in the United States and oil sands in Canada.

As a result, US gas production, having been flat around 65.5 Bcf/day during 1995-2005, rose steadily to 89.2 Bcf/day during September 2014. Of this, shale gas formed 5.5 Bcf/day in 2007, an amount which had reached 33.6 Bcf/day by late 2013, i.e. about 38% of all US production[7].

US oil production (all petroleum liquids), which had declined from about 9 million barrels per day in 2000 to a low of 7 Mbpd in 2005, rebounded to 14.2 Mbpd in August 2014. The corresponding change in crude oil plus condensate was from 5.8 Mbpd in 2000 to around 5.2 Mbpd in 2005 (with some interruptions by hurricanes), and up to 8.65 Mbpd in August 2014.

By contrast, Canadian production rose quite steadily through the period, from 2 Mbpd in 2000 to 3.4-3.6 Mbpd during 2014, and most of the growth was driven by oil sands, although tight oil production also expanded in the later part of that time.

This has in turn led to:

• A dramatic fall in US natural gas prices, increasing industrial competitiveness and leading to plans for liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports;

• A sharp reduction in net US oil imports, and an increase in crude and oil product exports;

• Dislocation of US oil and gas price benchmarks from global levels;

• A recent fall in global oil and gas prices, and a reduction in concerns about future availability of fossil fuels;

• Plans by other countries for unconventional oil and gas.

The rise of unconventional oil and gas has had a number of mostly indirect impacts on MENA. Light oil imports to the US have declined dramatically, which affects Algeria and Libya, but less so the producers of medium sour crudes. Saudi exports to the US have held up quite well, albeit sometimes at substantial discounts; most other Gulf producers concentrate on Asian markets.

Qatar’s LNG export plans were, of course, substantially affected by the rise of US shale gas and the disappearance of the North American market. Combined with the financial crisis, the country had to idle some of its newly-built LNG capacity in 2009, until it was able to divert cargoes to the higher-priced Asian market following the Fukushima accident.

The sudden abundance of cheap gas and natural gas liquids in the US also poses a competitive challenge to MENA petrochemical plants. Their advantage of cheap feedstock has been greatly reduced. And, with the exception of Qatar and perhaps Iran, MENA countries’ low-cost gas supplies are fully allocated – future production will be more expensive.

MENA itself has not yet developed unconventional oil and gas to any great extent, given its large conventional resources. However, Oman and Saudi Arabia, in particular, are looking to produce tight and shale gas to meet domestic demand.

But the key impact of unconventional oil and gas has been to add to global supply. LNG and oil prices fell sharply in late 2014, as fast-growing US unconventional oil supply and a resumption of production from shut-in Libyan fields coincided with poor economic news from Europe, China and Japan.

The growing self-sufficiency of the US had geopolitical impacts. With particular relation to the MENA region, these related to the proclaimed ‘pivot to Asia’ and to the US willingness to impose stringent sanctions on Iran.

The ‘pivot to Asia’ seemed to imply that the US military and security role in the Gulf would reduce, as its oil and gas exports were of less importance to the US economy. Indeed, the GCC countries were concerned about diminishing US involvement, and perceived the Obama administration to be weak and indecisive. But, with the rise of ISIS in Syria and northern Iraq, the US had again to play a significant role in the region, with the particular support of the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Ironically, it was also cooperating with Iran in fighting ISIS, while opposing it on its nuclear programme and its support for the regime of Bashar Al Assad in Syria. It became clear that, despite progress toward the much-touted US ‘energy independence’, the MENA region remained a vital strategic interest. Its oil and gas exports were still of critical importance to US allies in Europe and East Asia, as well as China – a strategic competitor but a major trading partner. The US military presence and alliances in the Gulf remained a potent, if unstated, threat to Beijing’s economic lifeline. The US, as consistently since the 1970s, sought to prevent the emergence of an energy monopolist in the region – the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s, Iran in the 1980s, Iran and Iraq in the 1990s, more recently Iran alone. It also had non-energy reasons – terrorism and its support for Israel – in remaining engaged.

As noted, unconventional oil was also key to the US policy to put pressure on Iran and bring it to serious negotiations on limiting its nuclear programme. Without growing shale oil production, it would not have been possible to remove 1 Mbpd or more Iranian oil from world markets without causing a severe price spike.

Key Factors of the Decade to Come

Over the next decade, some of these trends will continue, but others will moderate or recede. Slow economic growth in Europe and Japan, growing energy efficiency, increasing climate change action and falling costs of renewable energy will cause slower growth in fossil fuel consumption, particularly of coal but also of oil. A slowing of Chinese growth and reduced energy intensity of its economy is already moderating commodities prices. Faster growth in India under the new government of Prime Minister Modi will at most only partly offset this.

A period of lower oil and gas prices, as has occurred from late 2014 and may persist for some time, would reduce Middle East government budgets and pose a severe economic challenge to some countries. In the longer term, however, it would also encourage growing demand, and make high-cost unconventional and frontier oil projects less attractive compared to the Middle East’s large and low-cost resources. It would also be positive for MENA energy importers, notably Morocco, Jordan, Lebanon and Egypt, and particularly neighbouring Turkey.

Several MENA countries have the potential to expand oil production substantially if political difficulties are resolved, notably Iran, Iraq (both ‘federal’ Iraq and the autonomous Kurdish region) and to a lesser extent Libya. With Iran and Iraq having oil reserves in the range of 140-150 billion barrels each (and Iraq in particular having potential to find substantially more), only Saudi Arabia has larger conventional reserves. Expansion of production from one or more of these countries would be a threat to other OPEC members and probably lead to a more sustained period of weak prices.

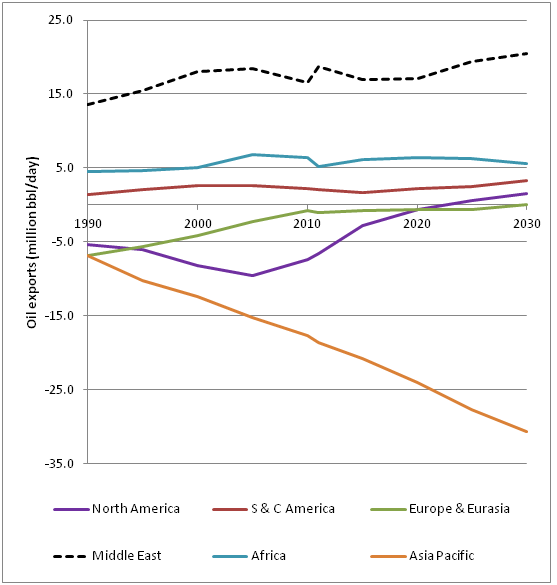

As Figure 3 shows, over the next two decades, Asia will extend its lead as the world’s largest oil importing region. The Middle East will remain the largest exporting region, but will not grow much as the call on OPEC output is flat or shrinking, and domestic demand take up a larger share of production. The major change is in North America which, from a large importing region, will move close to self-sufficiency or even net exports by the 2020s. However, this could be slowed if low prices reduce shale output.

Figure 3. Oil imports/exports by region (BP)

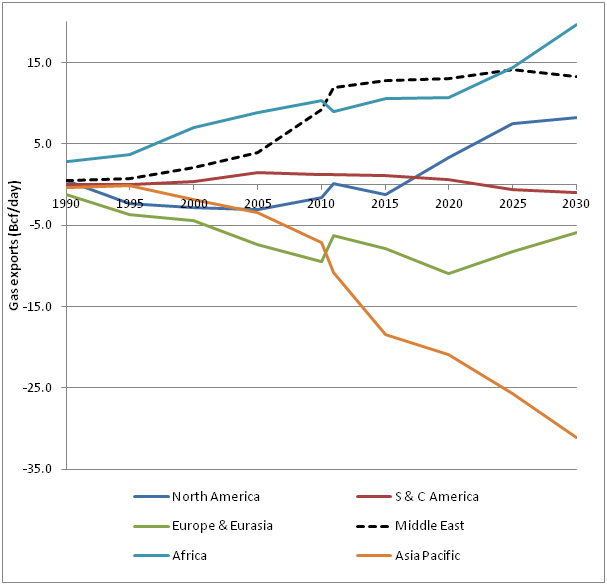

For gas exports, the picture is similar to oil, as shown in Figure 2. Asia is the main importing region, while the Middle East is currently the largest exporter. However, with little further growth from Qatar, and countries such as the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain and Oman reducing exports or even becoming importers, Middle East gas exports will not grow much, and Africa will emerge as a comparable or even larger exporter. The main exception is Iran, with the world’s largest or second-largest gas reserves, which has the potential to expand production substantially and to become a more important gas exporter, even though most of its gas is used domestically.

Figure 4. Gas imports/exports by region (BP)

Unconventional oil and gas will continue to expand. Lower oil and gas prices may slow its growth, but the technology continues to improve rapidly, bringing down costs. Other countries such as Argentina, China, Russia, Australia, Mexico, the UK and possibly Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Libya, may also become significant producers of shale oil and/or gas. US and Canadian oil and gas exports will help moderate global oil prices, as will new or growing sources of conventional non-OPEC oil and gas such as East Africa, the Brazilian ‘pre-salt’ and Kazakhstan.

More abundant and diverse gas supplies are already having an impact on global gas prices. Indexation of gas prices to oil is becoming less logical and less attractive to both consumers and – with falling oil prices – producers. It exposes utilities and traders to large price risks. Pricing against gas hubs is already well-established in the US, UK and more generally in north-west Europe. It will be challenging for an Asian gas price hub to emerge, although Singapore is attempting to establish an LNG hub and a suitable location in China is also a logical pricing point.

On the other hand, in MENA, administratively-set and usually very low gas prices are being revised up to reflect production or import costs more realistically. Gas prices have already been increased in Egypt, Oman, Bahrain and Iran. This will incentivise increased production and more efficient use, and will at some point feed through into higher electricity and water prices.

As over the past decade, “wild cards” could disrupt this picture. These are, by their nature, unpredictable but could include:

•A renewed economic crisis

Such a crisis might include China, causing a severe reduction in energy demand and prices. This may be similar to the 1997 Asian crisis or 2008-9 global financial crisis.

•Slowdown in non-OPEC oil and gas output

This may occur, for example, due to failure of the “shale revolution” to continue, leading to another sharp rise in global energy prices. It might follow a period of lower prices and underinvestment, hence repeating the upward part of the commodity price cycle seen in the 2000-2008 period.

•Development of a highly competitive electric/hybrid car which would reduce oil demand.

Oil remains the monopoly fuel in transportation. This is being slightly eroded by plans for more use of gas in ground vehicles and ships. But the unique convenience and energy density of oil has allowed it to retain premium pricing over gas and coal. The development of an electric vehicle which could compete with the internal combustion energy on cost, convenience and range would reduce or eliminate this premium pricing. However, oil is likely to remain essential for air transport.

•Political unrest and loss of oil exports from a major exporter or transit country

Possible candidates could include the Middle East or North Africa, as in the 2011-14 period. However, severe unrest, possibly including strikes, sabotage, terrorist attacks, revolution or civil war, could also affect a country such as Venezuela, Nigeria or one of those in Central Asia. This would lead to a renewed spike in oil and gas prices, and possible transitory interruptions of physical supply to that country’s main customers.

•Serious military conflict, e.g. in MENA, East Asia or eastern Europe

This would have uncertain impacts on global energy trade and demand. If it struck a major energy-exporting or transit country, or interrupted seaborne transit through important straits or shipping lanes, it would disrupt supplies and increase prices. However, if it affected major energy-importing countries, it could well cause global recession and falling energy prices, and so damage MENA countries even if they were not directly involved in the conflict.

•Severe climate deterioration or change in political awareness

A major climatic disaster, such as flooding, drought or hurricane, in a leading country, or signs of rapid climate change such as major ice-sheet melting, could lead to a change in political attitudes and much tougher action on greenhouse gas emissions. During 2014, with the US-China climate pact, the Lima climate change conference, and administrative action by the Obama administration, there were some signs that climate policy was moving ahead. Faster policy, such as carbon pricing or caps, would probably reduce demand for oil, but increase demand for gas in the medium term as it would substitute for coal. In the longer term, carbon capture and storage would need to be widely-deployed to reduce emissions from gas combustion.

Implications for the MENA region

Political unrest remains a serious threat for the MENA region given slow economic growth, political repression and large youthful populations. The resolution of the Iranian nuclear issue remains very uncertain, but could help in increasing regional stability. Continuing war and insecurity is likely to affect energy supplies, particularly from Libya, and also constrains the growth of output from Iraq. There is a small but not negligible risk of disruption in another major producer or transit route. However, these risks are somewhat mitigated by a better-supplied global market because of rising US output.

Energy demand in the MENA region, and particularly in the GCC, has been growing unsustainably fast over the past decade or so, because of the region’s economic boom, but also because of very low, subsidised domestic energy prices. This has become fiscally unsustainable for energy importers such as Jordan, Morocco and Egypt. Major gas producers Algeria, Egypt, Oman and Iran have all seen gas exports reduced or eliminated due to runaway domestic demand, while Kuwait and Dubai have begun importing LNG. Consequently, all these countries have implemented or are considering subsidy reductions, and the increase of domestic prices of petroleum products, gas, electricity and water. This carries some risks of political unrest, but has begun relatively successfully.

Because of fast-growing domestic demand, many MENA countries are looking to renewable energy and unconventional oil and gas. Several have also shown interest in nuclear power, with the most advanced programmes in Iran and the UAE. Energy efficiency has had a lower profile but may grow in importance as and when subsidies are reduced. Slower economic growth under the stress of lower oil prices may slow increases in energy demand, but government fiscal problems will also encourage the removal of subsidies. Already, officials in Kuwait and Oman have publicly linked these two issues.

Those MENA countries which are OPEC members (Libya, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and the UAE) have to consider their output policies, particularly in the light of planned growth of Iraqi exports, the possible return of Iran, and uncertainty of Libyan supplies. Saudi Arabia, with its Gulf allies Kuwait and the UAE, will be the key leader of that decision. So far, as at the OPEC meeting in November 2014, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have made it very clear that they do not intend to cut production, unless supported by other OPEC countries as well as some non-OPEC producers, and they believe a period of lower prices is necessary to rebalance the market.

In the medium term, Gulf OPEC countries could decide to continue high levels of production and hence lower prices, in the hope that this will encourage demand growth, reduce output from non-OPEC sources such as shale, and put economic pressure on some weaker OPEC members such as Venezuela and Nigeria. Alternatively, they could cut production to keep prices high, but this risks losing market share and so realising lower revenues ultimately.

Lower oil prices, if sustained, will have a severe impact on some regional economies. Iran, Iraq, Algeria and to a lesser extent non-OPEC producers Oman and Bahrain are vulnerable, and will need austerity programmes and/or foreign borrowing. The core Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) producers of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are in a stronger position given budget surpluses and large sovereign wealth funds and foreign currency holdings. However, they all – especially Saudi Arabia – have to confront the need for deep economic reform and diversification over the next one to two decades. Saudi Arabia, Oman, Algeria, Iran and others are also approaching uncertain political transitions to a new generation of leaders.

Falling oil and gas prices may seem to make energy security less important. However, continuing geopolitical uncertainty means that oil and gas supplies from the MENA region could still be disrupted. Similarly, possible covert or overt conflict with Russia increases the importance to Europe of accessing a variety of gas suppliers and import routes, with the Middle East and Caspian a key source. The key principles of energy security remain:

• Basic reliance on market-based mechanisms, avoiding where possible price controls, export bans and similar policies

• Strategic storage to cover short-term disruptions

• Emergency arrangements, such as those coordinated by the IEA

• A variety of energy sources, energy suppliers and import/transit routes

• Physical and economic resilience to shocks

• Multi-lateral and mutually-dependent relationships, between both ‘clubs’ of energy importers, and between producers and consumers

• Transparency and timely sharing of key energy data

• Military and diplomatic cooperation on physical security for important energy-producing or transiting regions

The MENA region will remain central to global energy over the next decade, even increasing its dominance of oil supplies to Asia. However, it faces growing challenges both on exports – particularly of gas – and domestically, from lower prices from energy sales, and economic and political difficulties. Energy consumers need to consider these vulnerabilities when planning their energy policies and strategies for diplomatic and security engagement with the region.