January 22, 2021

Chuto Dokobunseki

Oman's economic and fiscal stability in the post-Sultan Qaboos Era

Author

Dr. Hatim Al-Shanfari

Professor, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

Professor, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

Introduction

Oman has been transformed from absolute poverty in the 1970s to relative prosperity in half a century of economic development fueled mainly by the inherited wealth from oil and gas resources. The sustainability of this relative wealth is the main challenge in the future.

Sultan Qaboos Bin Said passed away on 10 January after almost half a century of leading the country and the succession of Sultan Haitham Bin Tariq was very smooth and quick, in spite of the anxiety about the resilience of the process before the inauguration on 11 January. There are three main challenges facing the new Sultan which are: establishing legitimacy, stabilizing the economy, and maintaining political neutrality in the region. The focus of this paper will be on economic stability and sustainability.

Historical Background

Sultan Qaboos Ruled Oman for almost half a century during which the country has transformed remarkably socially, economically and culturally. He managed to navigate through very tough challenges locally and regionally. His successful model in managing local affairs and establishing stable relations globally have won him great respect and a lasting legacy.

Oman was the only Arab country to have achieved 7 percent real economic growth or more over 25 years or more, according to El-Erian and Spence (2008). Only 12 countries in the world have achieved such a record after World War II.[1] The average economic growth of 7 percent in a decade leads to a doubling of per capita income and a drastic drop in poverty levels. Such achievement was attributed to good governance.

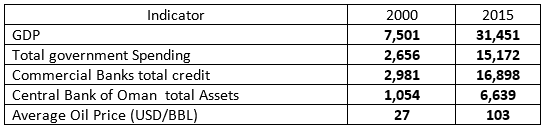

To illustrate the extraordinary transformation in Oman’s economy during a period of 15 years since the beginning of the 21 century, table 1 presents some selective macroeconomic indicators. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased by more than four folds, reflecting an upward trend in crude oil prices during this period. While the total government spending and commercial banks total credit jumped by 5.7 folds and the total assets of the Central Bank of Oman leaped forward by more than 6 folds in this period. Very impressive growth in these selective indicators. Other social indicators in health and education improved significantly in these 15 years’ period.

Table 1: Macro-Economic Indicators for Oman- Million OMR

Sources: National Centre for Statistics & Information, Central Bank of Oman, and the IMF.

The above indicators reflected an extraordinary economic boom period which is fueled by high oil prices. During this period, the government managed to accumulate healthy financial reserves in the sovereign wealth funds from the public finance surpluses. The accumulated wealth in this period was very tempting to increase government spending on infrastructure projects. This spending was relatively inefficiently managed. Moreover, the size of the public sector became very large and highly expensive to maintain in the last three years of this period. The year 2014 marked the peak of economic activities and government spending.

A Period of Low for long (2015 to 2019)

After 15 years of the impressive growth story in Oman and the region, 2015 marked a turning point in the economic performance of all GCC countries when crude oil prices dropped by 45 percent which resulted in a significant contraction of the nominal GDP and a big jump in fiscal deficits. The impact on Oman was much more severe. Many policymakers in the region viewed the drop in crude oil prices that started around the middle of 2014 and continued in 2015 as a temporary phenomenon. Unlike global major oil-producing companies that viewed the drop in oil prices as low for long scenario and accordingly started to adjust their expenses to deal with this new reality, governments in the region were anticipating that such a drop will be a short-term adjustment; like what was experienced in 2008 during the global financial, and accordingly it took a long time to make substantial adjustment in public spending.

Oman made a limited adjustment in government expenditure in 2015, which resulted in a huge jump in the deficit, that was mainly financed through drawing down the financial reserves of the past few years’ accumulations. These reserves were not part of the sovereign wealth fund assets. While the oil price dropped by 45 percent in 2015, the government's current expenditure was reduced by only 5 percent. As a result, the government deficit as a percent of GDP jumped from 3 percent in 2014 to 18 percent in 2015. While in 2016 the average oil price dropped further by 29 percent, government current expenditure increased by 2 percent, which resulted in an increase in the deficit to GDP ratio to a record 21 percent. The government debt to GDP ratio increased from 5 percent in 2014 to 13 percent in 2015 and further jumped to 32 percent in 2016, according to the Central Bank of Oman Annual Report 2018. The ratio of the current account to GDP was positive 5.8 percent in 2014 and one year later it was negative 15.9 percent. In 2016 this indicator was negative 18.4 percent. Double-digit twin deficits (Fiscal and current account) is a huge economic shock to manage for a country. Oman managed this shock by drawing from accumulated financial reserves and borrowing from foreign markets. The slow adjustment in government spending to the drop in oil prices in 2015 and 2016 was costly in terms of credit rating downgrading by rating agencies; like S&P and Moody’s. In these two years, S&P downgraded Oman three times and Moody’s twice. As a consequence, investors’ confidence in Oman’s economy was shaken and the cost of borrowing internationally became more expensive. Furthermore, money started to flow out of the local capital market as investors perceived that the economic risk started to rise.

Surprisingly, despite the huge accumulated fiscal deficit in 2015 and 2016 and the recognition that oil prices are likely to be low for long, the fiscal breakeven oil prices averaged around USD 95 per barrel for the period from 2017 to 2019. This was when the late Sultan Qaboos was getting very sick. The government was less willing to take major actions to address the fiscal imbalance to avoid any public backlash that can discomfort the very sick Sultan. Hence, there were sizable fiscal deficits that led to increasing the stock of foreign debt.

2020 End of an Era

Revenues from oil and gas make-up around 70 percent of the total government revenues in the last few years. There is a limited scope of increasing the share of non-oil revenues in total government revenues, through taxes and government services’ fees, without negatively impacting the economic activities of the private sector and consumers’ spending. According to the IMF's latest statistical indicators, the fiscal breakeven oil price for 2020 is estimated at around USD 105 per barrel, while the likely realized average oil price this year is USD 46 per barrel. This points to a large gap between the breakeven and the realized prices, which illustrate the magnitude of the challenge facing the government to balance the budget. Year to date, the average crude oil price has dropped by about 28 percent compared to 2019 mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic that has severely impacted both the supply and the demand globally. Unfortunately, there is usually a long gap in publishing monthly data in Oman, but for 2020 the delay is even more, mainly due to the negative outlook of the economy. As a result, the available monthly data of the year; especially on public finance, is only available for the first six months of this year. This makes it difficult to assess the impact of cost reduction measures that were implemented this year.

Furthermore, the IMF projected that Oman’s real GDP will decline by 10 percent in 2020, this is the largest drop in the last few decades. Moreover, the total government gross debt to GDP ratio will be at 82 percent compared to 63 percent in 2019, a huge jump just in one year. This debt to GDP ratio may not look that high compare to the standard in Japan or other OECD countries. But for a country like Oman, which is heavily dependent on natural resources that have very high price volatility, if this ratio exceeds 50 percent is considered very risky. Also, the total gross external debt as a percent of GDP is estimated by the IMF to be around 122 percent this year compare to 92 percent in 2019. The external debt represents public and private sectors borrowing from the global market in foreign currency; mainly in the US dollar. When debt is financed in a local currency, it is considered to be less risky for the economy compared to tapping foreign currency finance, but the local capital market is very small and shallow to raise funds for financing the government deficit. Another important indicator is the current account deficit to GDP ratio which is estimated to be around 15 percent in 2020. While a high public finance deficit leads to an increase in the debt to GDP ratio, a high current account deficit leads to an increased risk of devaluation for a country that has a fixed exchange rate with the US dollar; like Oman. Similar to 2015 and 2016, Oman is going to experience relatively extremely high twin deficits in 2020 and 2021, according to the IMF (2020).

As a consequence of the deteriorating economic indicates in 2020, attributed mainly to the COVID-19 pandemic, the rating agencies have further downgrading Oman several times this year. S&P downgraded the country twice; on March 27 and on October 16, Moody’s downgraded twice on March 5 and June 23, while Fitch downgraded twice on March 24 and August 17. All these rating agencies sighted rapid deterioration of fiscal and current account deficits and significant negative outlook in the next few years. Table 2 below shows the GCC countries' latest rating, as of December 8, 2020.

Table 2: Credit Rating of GCC countries.

Source: Ubar Capital (2020), GCC Fixed Income Report.

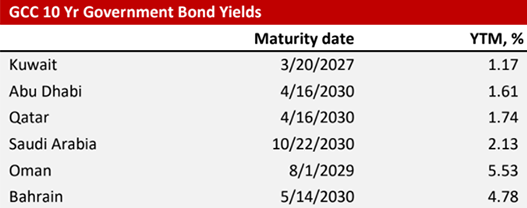

Even though Oman is rated a notch higher than Bahrain according to Moody’s and Fitch rating agencies, its 10-year government Eurobond yield is at 5.53 percent compared to that of Bahrain at 4.78 percent, which means that it is 16 percent higher than Bahrain, as shown in table 3 on December 8.

Table 3: GCC 10 Year Government Eurobonds Yields.

Source: Ubar Capital (2020), GCC Fixed Income Report.

This difference in the bond yields between Oman and Bahrain can be attributed to the investors’ perception about the financial backing of Saudi Arabia and UAE for the government of Bahrain, while Oman lacks such regional financial support. The cost of raising funds internationally has been steadily increasing in the past few years. According to Reuters news agency (2020), the government borrowed USD 2 billion one-year bridge loan from regional and international banks because it was not able to issue Eurobonds for this purpose. This bridge loan will be paid next year from issuing Eurobonds. It is the first time since 2016 that the government was unable to access the Eurobond market. The Financial Times reported on October 28, 2020, that Oman received USD 1 billion support from Qatar which has helped ease the concerns of investors about the borrowing risk of the country. Furthermore, the article stated that Oman is talking to UAE for possible financial support. This report from the Financial Times along with cost-cutting and revenue enhancement measures that were announced in October paved the way for Oman to issue USD 2 billion Eurobonds at a relatively higher cost in November and December. The budget for this year shows a deficit of USD 6.5 billion which will be financed through borrowing USD 5 billion, but this was before the pandemic and the crash of oil prices. The Pandemic made a difficult situation worse. There is no further public information on the size of the deficit after the pandemic in order to assess the impact on public finance.

Since inauguration day in January, Sultan Haitham has been very engaged in keeping on top of the fiscal challenges and he enacted a number of important reforms that were overdue in 2020. These include introducing the Value Added Tax (VAT) law that will be implemented in April 2021 at a starting rate of 5 percent. Also, an announcement of income tax that is planned for 2022, but not many details have been provided about this new tax. The proposed income tax in Oman would be the first to be announced among GCC countries. Furthermore, the government is considering to remove the subsidy on electricity for residential consumers starting in 2021; the economic cost of this subsidy is relatively high.

A medium-term Fiscal Balance Plan (2020-2024) was introduced in October to address the deteriorated fiscal conditions. The two main objectives of the plan are to boost government revenues and cap the growth of expenditure in order to achieve fiscal balance by 2024. The plan highlighted five pillars: Supporting economic growth, revitalize and diversify government investment returns, rationalize and improve the efficiency of government spending, establish and strengthen the social protection plan, and raise the efficiency of public financial management.

Given the severe contraction in economic activity in the past few years, there has been an increasing trend of terminating nationals who are working in the private sector. As a result, the government established a new Job Security Fund in August 2020. This fund will receive a contribution of one percent from the salaries of all citizens who are employed in the public and private sectors and one percent from employers, starting from January 2021. Also, there will be a contribution of 5 percent levied on new and renewed work permits of foreign works. The Fund has started to support laid-off nationals in November and after three years it is planning to provide financial support for nationals who are seeking employment.

After the Arab Spring in 2011, the government employed a large number of unemployed citizens in the public sector and increased the financial benefits for all the public sector employees. Since then, it was common knowledge that the public sector was becoming overstaffed, overpaid, and less productive. This year, the government decided to introduce non-voluntary early retirement for nationals who have completed thirty years of service in the public sector, as a measure to reduce current expenditure for which wages make up a large proportion. The average crude oil price this year would not be sufficient to pay the wage bill of public sector employees. It is estimated that for the government to be able to pay the annual public sector wage bill, the average crude oil price should be around USD 60 per barrel. But the average expected oil price in 2020 will likely be around 23 percent lower, resulting in severe pressure on the public finance to meet other budgetary obligations.

Privatization is one important source for financing the fiscal deficit, but for many years the government has been considering privatizing state-owned enterprises with limited success. Since 2015, there were only two privatized assets. The first was in 2018 when Oman Oil Company, which is fully owned by the government, sold a 10 percent stake in Khazzan gas field to Malaysia’s Petroliam Nasional Berhad (Petronas) for USD 2 billion. Khazzan gas field project is a joint venture between Oman Oil Company which used to own 40 percent and BP which owns 60 percent. Oman Oil Company's name has recently changed to OQ. Currently, both BP and OQ are interested in further divestment in Khazzan project. The second project to privatize was selling 49 percent of Oman Electricity Transmission Company, which was fully owned by the government, to the State Grid Corporation of China raising around USD one billion. This transaction was completed in the first half of this year. With the increasing pressure on public finance, the government will try to privatize more assets in the future.

Both the UK and the USA are providing a supporting role for Oman in this transition period to enact economic reforms that are overdue. They are both interested in creating political and economic stability in Oman. The UK has been supporting Oman by providing technical know-how and indirect financial support. This support is critical in helping Oman to secure non-commercial funds, like export credits.

Future Outlook

In spite of 45 years of economic planning that aimed to diversify the economy from very high dependency on oil and gas revenues, the government is more dependent on these natural resources as indicated by the high fiscal breakeven oil price of USD 110 per barrel in 2021, according to the estimation of the IMF (2020). This high dependency is likely to continue for the next 10 years unless a major transformation program is undertaken to diversify the economy. The country's proven reserves of these two natural resources are very small compared to other neighboring countries in the GCC region. The share of Oman’s proven crude oil reserves, which can be extracted economically, is estimated to be around 0.3 percent of the world’s total. At the current production rate, such reserves can last for about 15 years. Likewise, the share of proven natural gas reserves is around 0.3 percent of the world’s total and it can last for 18 years at the current rate of production, according to BP (2020). The likelihood of oil and gas production to continue longer than the indicated years is a reasonable probability, given the technological innovation that can lead to more future production at a lower cost. This issue, of lasting reserves, has been in the mind of policymakers and has created a sense of complacency that the country will not run out of these two commodities. But due to the climate change pressure and the significant drop in the unit cost of production for renewable energy both for solar and wind, the world is experiencing a rapid energy transformation from fossil fuel to renewable energy to meet the climate change goals that have been adopted in the Paris Agreement in 2015. Without a doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to speed up this energy transformation process, which implies high uncertainty and less economic stability for Oman.

Debt maturity and obligations are another serious challenge facing Oman in the medium-term. The first five years Eurobonds that were issued by the government in 2016 for USD 1.5 billion will mature in 2021 along with the bridge loan of USD 2 billion of 2020. Besides these two loans, there are various other debt obligations that will mature in 2021. The total debt maturity in 2021 will be around USD 6.4 billion, according to the Ministry of Finance’s Preliminary Base Prospectus issued on 19 October 2020 for the Global Medium-Term Note Programme document. Given the extremely high fiscal deficit that is projected for this year, it will be an overwhelming challenge for the government to repay the maturing old loans and finance the budget deficit for 2021; especially when the sovereign credit rating is not likely to improve during this year. Furthermore, the total debt maturing in 2022 will be around USD 6.1 billion, according to the Ministry of Finance (2020). Therefore, without further regional financial support to finance the budget deficit in the next two years, Oman will have very limited options to avoid going to the IMF for a rescue package. The country has tried very hard to avoid the IMF option in the past, but the heightened credit risk is likely to overcome such resistance. The IMF Article IV Review Missions have, in the past few years, been advising the government to control its unsustainable current spending and to enhance the non-oil revenues, without adequate response from the government. The IMF Structural Adjustment Programme, if implemented in Oman, will lead to severe economic contraction and sizable devaluation adjustment. Such shock will have a lasting impact on the social welfare of nationals. This explains the government’s reluctance to seek the IMF financial support.

Vision 2040 will start in 2021 with the 10th Five Year Plan (2021–2025). This vision was based on an extensive review of the past economic performance for the period of Vision 2020, which started in 1996 and has considered the external and internal opportunities and challenges facing the future of Oman, with the help of an international consultant. But from the preliminary document that was published on the Vision 2040, there is no sense of urgency to transform the economy in order to maintain stability and achieve sustainability.

The Fiscal Balance Plan (2020-2024) is mainly focused on enhancing government revenues, through introducing new taxes and government fees and reducing expenditures which are important but not sufficient to stimulate the growth of the economy that has peaked in 2014. These measures alone will likely lead to a further slowdown in economic activities. The government should emphasize attracting more investment; especially foreign direct investment, which can lead to productive job creation. Such investment can be financed through the proceeds from the privatization of public assets and by promoting pubic private partnership with foreign and local investors.

Conclusion

Oman, unlike other countries in the region except for Bahrain, will be facing significant economic challenges going forward. Some of these challenges are: first, limited crude oil and natural gas reserves that are likely to last for few years at the current rate of production, according to the BP Annual Statistical Year Book in 2020. Second, the cost of producing oil and gas is very expensive and annually increasing. Third, the consumption of crude oil and gas domestically is trending upward, which means that fewer resources that can earn hard currency will be available for export in the future. Fourth, the high volatility of oil prices will create very high uncertainty for the government income and spending programs. Fifth, the dominant role of the public sector in economic activities is leading to inefficiency and crowding out the private sector activities. Sixth, unemployment is on the rise and youth unemployment is relatively high. The public sector is fully saturated and has a limited capacity for any further job creation opportunities in the future. Furthermore, the private sector is very fragile and cannot create new jobs in the short to medium term. As a result, the prospect of creating new employment opportunities in the near future looks very challenging. Lack of employment opportunities can lead to social unrest and the experience of the Arab Spring in 2011 is still a threat looming across the region. Seventh, the accumulated public finance deficits since 2015, have resulted in huge public debt and a significant debt service burden. Eight, the energy transition from fossil fuel to clean energy globally, due to climate change, is likely to change the demand and lower the prices of these commodities that Oman is heavily dependent on. The economic stability of Oman in the medium to long-term will depend on the crude oil prices for which the country is a price taker, given the relatively low level of production. If the oil prices in the next few years remain below USD 60 per barrel, the economy will not grow and create job opportunities for the youth who make up a large proportion of the total population. Hence, economic stability will not be sustainable.

Since 1970, Oman has achieved a remarkable transformation in human and physical infrastructure which is a necessary condition for improving the welfare of its citizens, but it is not sufficient for maintaining sustainable economic prosperity in the future.

References

BP (2020), Statistical Review of World Energy, 69th edition.

BP (2020), World Energy Outlook, 2020 edition.

Central Bank of Oman (2019), Annual Report 2018, Oman.

El-Erian and Spence (2008), Growth Strategies and Dynamics: Insights from Country Experiences, Commission on Growth and Development, Working Paper No.6.

Financial Times (2020), Oman gets $ 1 billion in aid from Qatar, October 28,2020.

IMF (2020), Regional Economic Outlook, Middle East and Central Asia, Statistical Appendix, October, Washington D.C.

Ministry of Finance (2020), Global Medium-Term Note Programme, Preliminary Base Prospectus, October 19, 2020.

National Centre for Statistics and Information (2020), Monthly Statistical Bulletin, November Issue, Oman.

Reuters (2020), Oman secures $2 billion bridge loan: sources, August 12, 2020.

Ubar Capital (2020), GCC Fixed Income Report, 8th December, Oman.

[1]The 12 countries are Botswana; China; Hong Kong; Indonesia; Japan; Korea; Malaysia; Malta; Oman; Singapore; Taiwan; and Thailand.